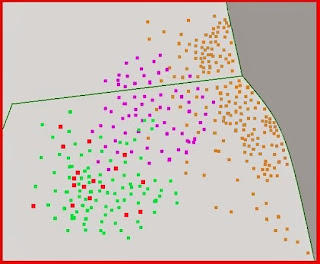

4.4: 'One-Layer sites'

There is a separate class of sites that need to be discussed here as they involve a whole series of other problems and investigation methods. Here the main evidence takes the form of the three-dimensional patterning of just the artefacts (and ecofacts) 'suspended' in a relatively homogeneous matrix that comprises deposits of geological/ pedological origin and may be a reflection of long-term environmental change. They are sometimes (falsely) called 'one-layer sites'. These mainly concern the archaeology of open-air sites of the Stone Age (cave sites were generally the result of other processes), but can also occur in the archaeology of other earlier prehistoric periods also. Here what has happened is that material that was originally lying on a ground surface has sunk into the material under them through natural pedological processes (such as worm-sorting [Link] *** or frost-heaving and other mechanisms). This may be accompanied by accumulation processes, such as a