6.5: Fieldwork on Surface Sites

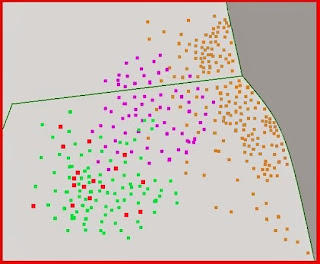

From the above, it is clear that detailed recording and analyses of the contents and patterns of surface sites can significantly contribute to our understanding of many aspects of life in thee past, from prehistory to modern times. This can be achieved during responsible artefact hunting, but part of the problem is overcoming the difference between what the average collector considers collectable, and archaeological evidence. Much of the latter has often simply been bypassed in Collection-Driven Exploitation of the archaeological record (see ****). The issue is not only whether the artefact hunter gathers every artefact visible on the surface of a field. The issue is a little more complex. This diagram illustrates a fictional surface site with the distribution of four types of artefact across it (shown by the different colours):

It represents a ploughed site in two separate fields next to an area of pasture (where no surface finds can be found and plotted). There are four discrete scatters of finds in the ploughsoil relating to three separate archaeological events or processes on that spot in the past. They might be separate phases (first century AD Roman, 3rd century Roman), they may relate to zonation of activities (one scatter might be slag and fired clay, another roofing tile from collapsed wooden buildings). An archaeological field survey would grid-walk such a site and analyse the scatters - for example it looks like the orange spots might be restricted to a rectilinear area, and perhaps the scatter going down towards the bottom right corner is the upper fill of an enclosure ditch (check the cropmarks, geophys). The distribution suggests that the site continues into an adjacent field - which has heritage management implications. The orange and purple finds have a mutually exclusive relationship, and could represent two different activity zones. The red finds seem to have a distribution that matches that of the green, so it seems that the two might in some way be in association. The establishment of the current field boundary seems likely to be later than all three spreads, possibly ploughed-out features are represented by the scatter, and so on.

We may consider the results of an artefact hunter going onto those two ploughed fields with a metal detector and starts looking for collectables and removing them. The metal detector does not detect fired clay, tile and pottery, or bones or anything else like that which is also a component of those scatters. The metal detector user's main interest in the slag is going to be that its going to throw their signals out and they'll be cursing it by the end of the day if it is not possible to set the detector to discriminate it out, yet some of that slag is very characteristic of a specific smelting process. Not collecting those pieces loses a piece of information about what was happening on that site. If the metal detector user fails to stoop to pick up the two small brown corroded iron lumps and take them home to place under their domestic radiographic unit, they are not going to find out that this was one of the very rare sites in the region with Roman chain mail on it. In fact they came from a ploughed-out cremation preceding all the other activity on the site, another piece of information about what the site was used for (which the artefact hunter would most likely not spot as the cremated bone is in small pieces and does not produce a bleep on the metal detector).

If we imagine that the spreads are more discrete, and in them are diagnostic metalwork finds, some buckles, strapends, tools, coins - something which can suggest a date for the associated material, or perhaps say something about what was going on at this site (military equipment for example). That is precisely the kind of material that the metal detector is is going to put into the finds pouch at once. Anything like that is precisely what a collector is looking for. Taking it away however, totally obliterates any chance that any subsequent examiner of the site can find that information. It may be argued that if any given find is one of the one-in-five currently reaching and recorded by the PAS, the co-ordinates of the findspot might accompany the object. It might be, but unless it has a very accurate pinpoint (not all metal detected finds do), then it is next to impossible to associate it years later on the basis of the PAS records with any other finds from that site. This includes random loose objects collected by the same artefact hunter at various times over the previous two years, by other artefact hunters who visit the site and also report finds, or a systematic gridded archaeological survey carried out by an amateur group or mitigation activity by professionals in advance of development.

The main point is that, depending on what kind of archaeological evidence these spots represent, in most cases it is not going to be possible to analyse these scatters 'live' in the field and plot them straight onto a map. It might be possible if they represent obvious categories, samian versus amphora sherds, Early Iron Age versus willow-pattern, but even so, the individual finds should be bagged up individually (or at least by grid) with the co-ordinate clearly associated with each piece or group of pieces of evidence.

|

| Individually bagged finds |

|

| Results of artefact hunting and selective pickup - not data |

How many artefact hunters' personal artefact collections contain the full range of artefactual evidence from even one site collected according to its detailed distribution across the site and stored in a manner allowing the analysis - and re-analysis of the patterns? The answer to that question will allow us to approach the answer to the question about what the difference in approach is between how an archaeologist sees the sites that artefact hunters exploit in their search for collectables, and how they see them. It also goes some way to explaining what would be constitute responsible artefact hunting on sites like this.

Adapted from two posts on the PACHI blog: Thursday, 6 March 2014, Focus on UK Metal Detecting: What's this all about? UPDATE 7th March 2014: Focus on UK Metal Detecting: Not Doing the Service to History People Say'.

Tamara Kroftova comments:

"The claim that simply removing material from the surface of an archaeological site or assemblage is not damaging the archaeological record is so obviously false, one wonders why it is so frequently trotted out as an excuse for irresponsible collecting. All over the country, segments of the cultural landscape are being stripped of their evidential value, without record, without mitigation, and what is worse, leaving nothing behind to show later researchers that a given site has been 'done over;' by collectors and to what extent (let alone what was taken from where). This is just wanton destruction".

Comments

Post a Comment